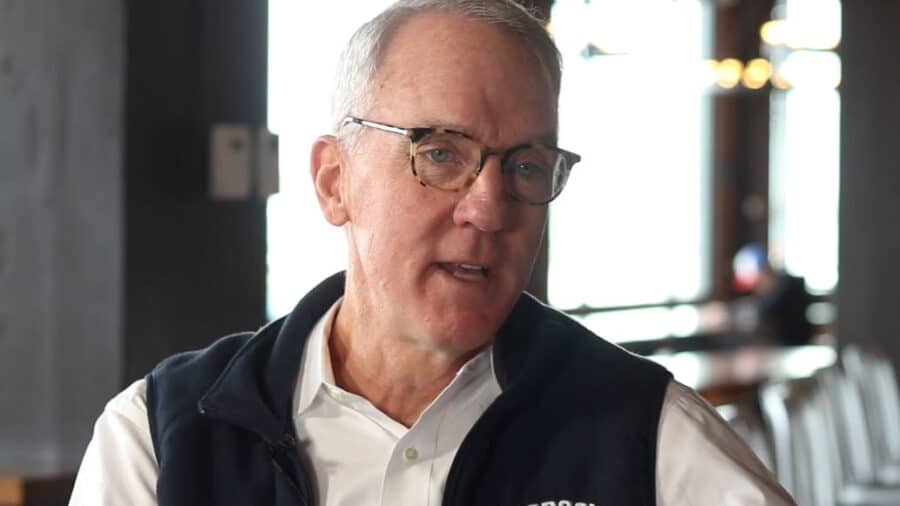

Richard Levin is an esteemed executive coach, and the founder of Richard Levin & Associates, one of the most recognized names in the field. He has a doctorate in psychology and education, with more than 30 years of experience coaching executives.

Richard Levin & Associates recently merged with the Center for Applied Research (CFAR). A management consulting firm borne from a Wharton School research center, CFAR helps leaders “activate their organizations to achieve their highest aspirations.”

I had the pleasure of talking with Richard about his background in psychology, his illustrious career, and a few of his inspirations. We also discussed some of the keys to building dream teams—and coaching talent to greatness.

A background in psychology

I started our interview by asking Richard about a rather special connection. When my business partner Daniel and I purchased The Predictive Index in 2014, we inherited a company with 60 years of history in psychometrics and behavioral science.

For PI, that history began with Arnold S. Daniels, a former U.S. Air Force flight navigator who’d led his team through more than 30 missions during WWII—all without a single casualty. Daniels later joined a scientific study to find out what exactly made that team so successful. In doing so, he discovered a love for psychometrics, and created the first Predictive Index Assessment.

While I never had the chance to meet Daniels, Richard did. Though the two didn’t know one another well, they too shared a crucial connection.

“He was in the Air Force with my father,” Richard explained. “When I was first exploring the study of psychology—whether I should become a psychologist or not, which direction to go—my dad said, ‘Why don’t you call Arnold?’”

In many ways, Arnold Daniels was a coach’s coach, before executive coaching even existed. According to Richard, Arnolds saw the power of psychology and how it could shape the world.

“He saw possibilities. It wasn’t just the therapy kind of psychology, which is where I started, but how psychology could be applied—to the workplace, to human behavior in general, to the political system, to everything.”

A pioneer in executive coaching

Just as Arnold Daniels paved the way for applied psychology in the workplace, Richard has been instrumental in shaping the executive coaching profession.

Richard is widely recognized as one of America’s first executive coaches. He founded Richard Levin & Associates in the 1980s, back when the notion of helping executives and senior teams “up their game” was largely unheard of.

“If you wanted to become an even stronger leader, or a more motivating and inspiring leader than you already are,” explained Richard, “you would hire a coach to help you get there.”

While self-motivation can be a powerful reason to reach out to a coach, there are other times when the need is more extrinsic. For example, a CEO may identify a high-potential SVP and hire a coach to help them grow into a C-Suite position. According to Richard, these can be extremely rewarding situations, but also delicate ones.

“If that high-potential leader agrees, and has the appetite to become even stronger, it plays in beautifully, because that’s the ideal person to be coaching,” he explained. “But if somebody is told, ‘You’ve got some rough spots, so we’re going to have you see a coach,’ that seldom works.”

What makes a good executive coach

One of the most important factors in a successful coaching engagement is chemistry. Executive coaching is typically a 1-on-1 dynamic, so it’s crucial that executives find a coach that fits their needs.

According to Richard, that starts with the proper expertise—something firms like CFAR all but guarantee. “Over the years, we have figured out who’s likely to become a great coach. And we’ve done that vetting for you as an executive. Finding that independent coach through a firm like ours makes it more likely you’ll find somebody who is excellent.”

Just as critical, however, are the interpersonal dynamics behind the relationship. How do you find a coach you can listen to and learn from—not just for business development, but for personal development?

“That’s really the secret ingredient,” said Richard. “We should not be looking at this firewall between the personal and the business side. What we’re trying to do is encourage somebody to bring their whole self into the workplace.”

In many ways, business and personal well-being are two sides of the same coin. The discipline of talent optimization—putting the right people in the right roles for the right business needs—is proof of that. Only by respecting the relationship between the two, then, can a coach thrive.

“You can’t check yourself at the door and say, ‘OK, now I’m in work mode.’” Richard explained. “Capturing the essence of who the person is, and developing all parts of themselves—that’s the best kind of coaching engagement.”

How to measure coaching success

Metrics are a critical facet of any coaching relationship. For an executive to show growth over time, they need to know exactly what they’re striving toward—and take measurable action.

“You want to be measuring against something,” Richard continued. “As a coach, you want to identify with the person being coached: How will we know we’re getting there? How will we know we’re being successful?”

I brought up something I’m actively working to improve: my listening. Curious, I asked Richard how you could measure “better listening” from one coaching session to another.

“Well, what are you listening for? What are you trying to hear?” he shared. “Are you drifting off somewhere, or is your mind racing and something else is going on?”

To explore these questions, Richard might task a CEO like me with interviewing someone else in the organization and “really focusing” on what’s said. I’d then come to the next coaching session ready to share my experience.

“Did you feel more in the moment?” posed Richard. “Did you feel more present? What felt different?”

My answers to these questions can make for valuable data points. But according to Richard, there’s even more data to consider when you bring more people into the equation.

“You’re looking for objective data or feedback that says, ‘Here’s how others perceive you.’ At the beginning of the engagement, others perceive you as not such a good listener. After six months of coaching, we do another assessment and find out that, wow, you’ve come a long way.”

Picking the right engagement tools

Measuring perception may seem daunting, but in the current age of analytics, it’s more intuitive than you may realize. According to Richard, it’s all about having the right tools.

At CFAR, Richard’s team uses a proprietary 360-interview tool to measure sentiment. They also make use of assessment tools, including The Predictive Index. “PI is one of the cleanest and easiest to use, and gives you really good data to spring off from.”

With a 360 tool, a coach like Richard can solicit candid feedback on an executive from a variety of sources: a peer, a direct report—even a loved one. “You want people whose input you really value and trust.”

By layering on a platform like PI, which provides objective data on a person’s workplace drives and needs, the coach can identify natural opportunities for growth. As Richard put it, “Let’s not just focus on development, or negatives. Let’s talk about somebody’s strengths that can become greater strengths.”

Playing to a person’s strengths

In 1996, I had the honor of coaching the U.S. Olympic Sailing Team in Savannah, Georgia. During my time in Savannah, I had the opportunity to meet with other Olympic coaches at the height of their fields. Perhaps most memorable was Tim Gullikson, coach of the legendary tennis player Pete Sampras.

Winner of 14 Grand Slams and 64 career titles, Pete is perhaps the last great “serve-and-volley” player to grace the sport. His entire game was set up by his overpowering first serve, which allowed him to run up to the net for a decisive follow-up shot.

When I met Tim, I asked him about his strategy as a coach, and how he’d found success. He shared that he and Pete spent 90% of their time working on Pete’s strengths, and only 10%, by comparison, on his weaknesses.

When Pete’s first serve wasn’t going in, he was mortal. But when his first serve was stingingly accurate, he could beat anyone in the world. So Gillikson was like, “Why wouldn’t we work on the first serve?” For me, that was a really heartening moment—hearing that great coaching can be both data-driven and aspirational.

I shared my story with Richard, who agreed with the sentiment. “You’re playing to somebody’s strengths. They’re coming to me as a coach because they want to be better at their game, whatever their game is.”

Embracing talent optimization

CEOs have a lot to juggle heading into 2021. According to the 2021 CEO Benchmarking Report, 53% of CEOs say their No. 1 priority is strategy development. Another 20% say they’re focused on operational execution.

Between daily operations and strategy planning, CEOs may feel they’re prioritizing what’s right for the business. But they also shouldn’t neglect that human element of the business. After all, people ultimately oversee operations and see strategy through.

“I hope we’re not talking about a CEO who just sits in her or his office all day long and doesn’t interact with anybody,” said Richard. “Then we’ve got a different set of issues.”

“You have a vision as a CEO,” he continued. “You’re using basic human behavior skills to be able to get from A to B. It’s looking at the personal and human side as part of the equation, not separate from it.”

That’s the essence of talent optimization. By aligning talent strategy with business strategy, you can build dream teams that play to their natural strengths. Start each day by bringing your best selves to work, and end each—like any great sports team—by leaving everything on the field.

How to grow as a leader

I ended my interview with Richard by asking what he values most in a coaching relationship. And, natural mentor that he is, Richard turned the question back on me. What do I value most?

Personally, I went to a coach for a very specific reason. Jim Allen, a friend working at Bain & Co., had introduced me to a framework called “Front of T-shirt, Back of T-shirt.”

As a leader, the front of your T-shirt represents your strengths. These are the adjectives you use to describe yourself, and imagine others would use to describe you too. The back of your T-shirt, meanwhile, represents the qualities you don’t see about yourself. These are the adjectives your peers would use to describe you when you’re not in the room.

I went to a coach to discover what was on the back of my T-shirt. And while I’m still working on those elements, having that outside perspective—someone who could see what I couldn’t possibly see—has helped.

For leaders looking to learn and grow, there’s no amount of stretching or looking in a mirror that gets you there. It needs to be an objective third party who cares enough to really take you on this journey, even if it means dealing with some hard truths.

“You want a coach who can lift that person up, dry the tears off, and say, ‘OK, now that you’ve experienced what you have, what are you learning from this?’” said Richard.

For more on my conversation with Richard, check out our video interview.