A response to the recent NYT article on personality assessments in the workplace

In an Aug. 22 editorial in the New York Times, Quinisha Jackson-Wright made a claim that personality assessments undermine inclusivity. This claim was based on a personal anecdote generalized as truth. However, the writer’s not alone in her experience which is exactly why—as an organization with deep roots in industrial-organizational psychology and psychometrics—we wanted to address these claims and share a different perspective on the real issue at hand.

Before diving in, we want to acknowledge that Jackson-Wright may very well have had a poor experience with an employer and the use of the Myers-Briggs personality test. This isn’t meant to invalidate her experience, but rather to shed light on where the blame really lies: misuse of assessment results and assessments unfit for the workplace. When companies invest in high-quality, scientifically validated behavioral assessments and use them properly, inclusivity is actually nurtured, and the talents of every employee are optimized.

The real problem

Different assessments have varying levels of breadth and depth, as well as different applications, as noted in a 2018 Scientific American article. Some are more granular than others, and some companies—like The Predictive Index®—only focus on a subset of traits proven to be relevant to workplace behaviors.

Invalid behavioral assessments

One concern Jackson-Wright shared was about vagaries in score interpretations—meaning two people may interpret the same results differently. If this happens when reviewing the results of an assessment, that assessment has a validity problem. Validity refers to the appropriate interpretation and use of assessment scores. High-quality behavioral assessments use validated reports, application tools, interpretive materials, or training to ensure interpretations and uses are standardized and accurate. Results should always be interpreted the same way.

The writer also focuses the discussion on one tool—the MBTI—which is not validated for workplace selection and is poorly regarded amongst serious practitioners of psychology and psychometrics. Some assessment companies prey on ignorance without even trying to meet basic standards of validity, reliability, and fairness. Reputable companies hold themselves to a higher standard and work hard to provide validated, actionable resources that improve the workplace for everyone.

Misuse of behavioral assessments

Dr. Sarah Gaither, a researcher Jackson-Wright interviewed for the article, talked about “weaponizing” scores, or using them to discriminate against a candidate or employee. Any tool, when misused, can be dangerous. This is not intrinsic to all behavioral assessments. A well-built assessment system will prevent such misuse so clients know how to use scores appropriately and productively.

Moreover, personality measures should not be used as a crutch. Personalities shouldn’t serve as an excuse for unprofessional or inappropriate behavior—just like they shouldn’t be the sole factor in promoting and hiring. People are total packages. Personality assessments provide valuable information about needs, drives, and behaviors, but all teams are comprised of real people. Any assessment worth its muster will account for the person behind the test.

Why understanding behavior matters

Understanding workplace behavior is critical for job fit, proper management, and teamwork. Behavioral assessments allow people to better understand what drives them in the workplace, ultimately allowing them to find a job that’s a natural fit for their personality.

These assessments also provide insights that support manager interactions with direct reports. When managers are aware of differences, they can manage people better so they can continue to thrive—even if they’re not wired quite like the rest of the team.

For example, PI, as an organization, is very dominant and extraverted. But my team needs to work slowly, quietly, and steadily. As a result, my team has an office separated from the open floor plan where the more extraverted teams operate. This quiet, more private space lends itself to the personalities of my team.

Jackson-Wright shared a personal example experience about a time a manager dropped work on her desk without any instruction. When they responded assertively, the writer was reprimanded for being unprofessional. This anecdote is a great example of why we need self-awareness—which can be gathered through behavioral assessments—in the workplace. With a better understanding of each person’s needs and working style, Jackson-Wright and her boss could have had a more amicable discourse.

This is why properly administered and scientifically valid behavioral assessments promote inclusivity. When high-quality behavioral assessments are used as intended, they make people aware of their differences and provide a common vocabulary from which to communicate. Having the vocabulary forms the basis of understanding, but it can only come from self-awareness and a willingness to lean into personal growth.

The science behind behavioral assessments in the workplace

Personality isn’t just how we interact. The writer claimed “personality traits do not directly correlate with work capabilities,” but there are decades of research (like this and this) showing how personality relates to performance in a variety of jobs. When measured alone, personality isn’t the strongest predictor of performance. But when personality and behavioral data is combined with other sources (e.g., experience, cognitive ability, structured interviews) and compared to the specific demands of the job role (not the dominant company culture), a more objective and inclusive hiring process is achieved.

Consider the U.S. government’s O*NET database, which lists 16 work styles and 41 work activities—most of which are behaviorally driven. When users navigate careers on O*NET, they see statements like “Job requires accepting criticism and dealing calmly and effectively with high-stress situations” or “Job requires being careful about detail and thorough in completing work tasks.” These are behaviors related to personality, but they’re not the only requirements for getting the job.

Why culture fit matters

Jackson-Wright wrote “culture ‘fit’ matters more than it should,” and added, “personality assessments may be one of many practices that unintentionally isolate or penalize those who prefer to work in isolation or silence.”

These statements can, and should, be addressed separately.

Culture fit is when an employee or candidate is aligned with the organization’s core values and company culture. This fit plays an important role in businesses being able to execute their strategy. Poor culture fit is also one of the top drivers of turnover. For these reasons, culture fit matters.

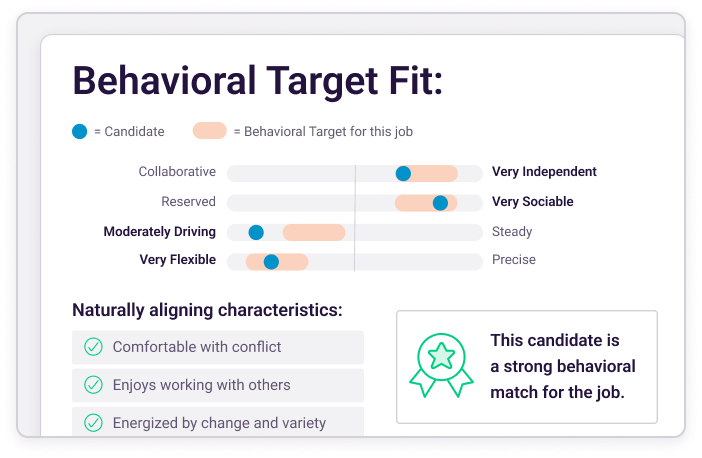

With regard to introverted employees, the work environment is perhaps even more important than culture fit. An introverted person will expend more effort and energy adapting to a high-extraversion, collaborative environment or role than a naturally extraverted person would. A company trying to fit square pegs into round holes by placing candidates in misaligned roles will consistently cry foul when the candidate they hire is a poor fit. Companies using behavioral assessments correctly have this less frequently as new hires are aligned with roles suited to their workplace needs and drives.

Behavioral assessments can be used to make introverts feel at home. We don’t hire people because they’re just like everyone else in the organization. We hire people for a job—and different jobs have different behavioral demands. Introverted people are needed at every company. By being able to identify who’s extraverted and who’s introverted, managers can better support people who may not match the overall culture. We call this culture add—when you start to diversify the personality of the organization to support its growth.

Introversion in employees and leadership

Jackson-Wright stated introverts in the workplace are at a disadvantage. While American culture may value extraversion or dominance, introverted job roles are still relevant and in demand. For example, in a sample of nearly 7,000 Job Targets in our software, nearly half (47%) are looking for low extraversion candidates.

Introversion also doesn’t exclude individuals from assuming leadership roles. Here at PI, 20% of our executive team is introverted—including me. Personality doesn’t determine whether you will lead, but how you will lead.

One experience is not representative of them all.

Jackson-Wright clearly had an unhappy experience with her former employer, but the blame falls on the people who misused a poorly-built personality assessment—not on the existence of personality and behavioral assessments or even the assessments themselves.

We agree assessments that are poorly built or used improperly can cause harm—but this is true of any tool. When companies invest in high-quality measures of personality that are supported by clear, simple, and accurate systems for using those scores, inclusivity can be improved.

By measuring, naming, understanding, and responding to each other’s personality differences, diverse personalities can work productively and compassionately together. Companies also benefit because people can be matched to jobs where their personality is a strength—promoting engagement and discretionary effort.

The discerning reader of Jackson-Wright’s editorial will conclude that the answer to promoting inclusivity is actually more behavioral assessments, not less.

Join 10,000 companies solving the most complex people problems with PI.

Hire the right people, inspire their best work, design dream teams, and sustain engagement for the long haul.