Olivier Aries is Vice President of Professional Services at The Predictive Index. Previously, he stood up and led the global security and disaster recovery program for Kearney, a management consulting firm; he led the firm’s response to the Zika virus crisis, the Paris terror attacks, and multiple safety and security incidents. He is also co-founder of a Pentagon-funded deep tech venture developing autonomous solutions for emergency casualty management on the battlefield.

There’s no way to know how dire the economic context will be when you read this.

In fact, this uncertainty determines the essence of disaster management: how to acknowledge, and adapt to a highly fluid situation, blunt its worst impact, and maintain continuity of governance and operations.

Merriam-Webster defines a disaster as “a sudden, calamitous event bringing great damage, loss, or destruction.” This definition encapsulates the two most important dimensions of disaster management for which executives must prepare:

- Speed of change

- Scale of change

Speed of change matters because executives normally control the pace at which their business operates. They proactively determine what happens when—from manufacturing capacity investment plans to the date of the holiday party. They typically have time to think and plan. In normal times, the standard business units of time are the week and the month.

When disaster strikes, two things happen: First, executives are stripped of their ability to control the pace of events. They are relegated to a reactive role. Many struggle to acknowledge and adapt, because thinking fast is hard, and because their ego is hurt. Second, high-stakes decisions must be made in a highly compressed time frame. In disaster mode, the standard business units of time become the hour and the day.

In life-or-death situations, such as deciding between emergency treatment options for casualties, the decision unit of time shrinks to the minute.

Scale of change matters because humans are adapted to living in an environment in which a few things change and a lot of things are stable. For example, the weather changes, people’s schedules change; but availability of power, the internet, access to transportation and food are assumed to be constants.

A disaster reverses the change equation: Many things change, and only a few things remain stable. Decisions must be made at scale and amid a level of complexity where most people, including many executives, do not usually operate.

More importantly, during a disaster, people change.

Uncertainty and fear move cerebral activity from the frontal cortex, where normal higher-level executive functions reside, to the limbic system, also known as “primal” brain. The limbic system triggers threat responses: fight, flight, or freeze. None of them are adapted to a thoughtful crisis response. Disaster preparedness aims at minimizing fear so that executives can continue to respond to the situation (i.e., operate rationally) instead of reacting to events (i.e., be governed by emotions).

Most disaster contingency and continuity practices do not aim at mitigating external change itself. They aim at mitigating people’s irrational reactions to rapid change and bolstering executives’ ability to manage faster and bigger external change in a rational manner.

In my practice, I found the ATSC framework critical to managing disaster:

- Anticipate

- Team up

- Stop the bleeding

- Communicate

1) Anticipate

Anticipate external change.

Use scenario-planning techniques and prepare for the worst-case scenario. If your leadership team expects a drop of activity of 25%, model for 50%. If your leadership objects to this approach, ignore them. Companies, like countries, teams, or families and all human constructs, can and will fail given the wrong combination of circumstances.

Run table-top simulations.

Armed forces use these because they work. I have seen some CxOs sweat and others freeze when presented with dire choices and no time to decide. Simulations have a double benefit:

- They pressure-test your continuity plan and highlight preparedness gaps

- They allow your leaders to experience, feel and practice:

- Experience: “What happens when we are thrown in the crucible?”

- Feel: “How do I respond in an emergency?”

- Practice: “Are we following the preparedness plan?”

Practice is vital. Don’t let the real disaster be your leaders’ first disaster.

2) Team up

Set up a separate crisis management team.

Why do that? Because it’s critical to insulate the top leaders from the day-to-day, tactical response actions. A crisis is taxing and you want your leaders to stay mentally available and agile to continue to make the right strategic decisions.

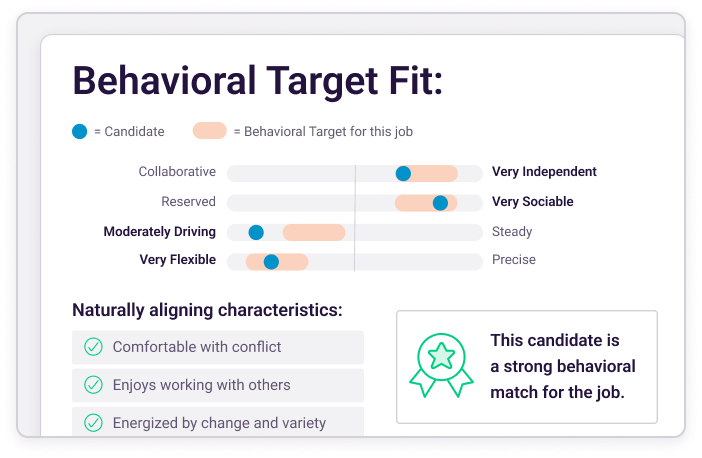

Balance behaviors.

You increase your odds if your response team is behaviorally balanced to:

- Make decisions with imperfect information and data.

- Rigorously assess risks.

- Make timely decisions.

- Be thorough and organized.

- Overall, be nimble, and self-aware.

Train your team to be self-aware, to be aware of each other’s behaviors, and to determine:

- How they communicate

- How they will make decisions

- How they will take action

Factor in the behavioral make-up of your executive team: If they are innovators and risk-takers, they will jump to action, even when analysis is first needed. If they are “stabilizing” profiles, comfortable with processes and data, they may get paralyzed.

So, you must speak truth to power and run training and coaching sessions with your C-suite to make them realize how their own behavior may empower or inhibit the response team.

Set up a resilient governance.

Especially in a pandemic, anyone may become incapacitated, including your CEO and half of the response team. So you need to ask the hard questions and develop protocols accordingly:

- Who makes the decisions if the C-suite is sick, or unreachable?

- How do we decide if we disagree?

- How does the team convene and communicate in degraded conditions? What if the internet stops?

3) Stop the bleeding.

The military calls it the “golden hour” – this is the short window of time during which a battlefield casualty can be saved if proper emergency procedures are applied. In many cases, it’s about stopping the bleeding at all costs.

The same goes for a business emergency. As an executive, you have to first focus on what is your biggest, most immediate threat. It may be cash; it may be repatriating your most exposed employees; it may be containing a confidentiality breach.

Regardless of the disaster, make the tough decisions now. Too many high-stake decisions are made too late. You easily see why: In a crisis, you don’t have the data you need; you may not have the right team around you; you may be paralyzed by the possible impact, or by your responsibility if you make the wrong call. Trust me: The wrong decision made early can always be reversed; the right decision made too late can be lethal, or at a minimum, devastatingly expensive.

4) Communicate.

What is the most precious commodity in a disaster? No, it isn’t time (although it’s a close second). It’s reliable, steady communication.

In a disaster, sharing information serves multiple goals:

- Communication calms people and gives them control.

- Communication helps people make informed decisions.

- Communication shows you care.

- Information compensates for the breakdown of regular organization and social structures.

Keep it simple.

Good crisis communication follows simple rules:

- Be frequent – a daily cadence is often the right cadence, at least initially.

- Be concise – focus on facts.

- Be relevant – focus on what matters for your audience.

- Be consistent – don’t underestimate the comfort of seeing the same faces every day.

- Be honest – don’t make false promises; explain what is known and unknown.

- Be confident – people look up to you for leadership; speak accordingly.

- Be compassionate – acknowledge that people are struggling.

Adapt to your audience.

Different types of audiences have different needs, and process information differently. Executives (yours, your clients, your suppliers) tend to be action-oriented and focus on agency and decision. Employees with “stabilizing” profiles in finance or manufacturing roles need plans, details, data, and directions. Use behavioral information about your audience, when available. It will pay a dividend in clarity and trust.

Rise up to the occasion.

Every crisis is unique. And yet it triggers organization and behavioral disruptions that can be entirely anticipated. To quote Jeanie Duck, the change management expert: “If it is predictable, it is manageable.”

By following the practices discussed earlier, you can be a fully prepared executive, able to anticipate events, maintain control in the storm, and demonstrate your steady leadership while others will falter. Doing so, you will play an active role in building the resilience of your organization, your employees, and your community, and accelerate their return to normalcy.