Every business, no matter its size or industry, is being tried by COVID-19 and its social distancing mandates. Through office closures, revenue shortfalls, or children complicating attempts to work from home, we’re all being forced to adapt.

Leadership mettle is especially tested in times of crisis. There’s an expectation that as the figurehead of a firm or branch, you display poise, decisiveness, insight, and empathy—often all at once. It’s a nearly impossible task, even for the most energetic and charismatic leaders.

Those who recognize the limits of their capacity will be better equipped to adapt, realign, and rebuild their teams, displaying resilience amid the storm. That means exercising self-awareness: understanding your strengths and when you may be leaning too heavily on them.

To avoid this critical pitfall, you’ll need to first grasp:

- How behavioral drives can be amplified in times of crisis.

- How stretching those behaviors can become problematic.

- How to balance your behaviors with a well-rounded leadership team.

Understand how your drives are amplified in crisis.

In any time of heightened pressure, our instinct is to revert to our most natural behaviors. This holds true across any organization, regardless of position or pay grade.

“This is a direct result of how drives, needs, and behaviors work,” explains PI Certified Partner Rob Friday, Managing Principal at Predictive Success. “Under times of stress, people revert to [their] core. You have probably heard that people have a fight or flight response when faced with danger. This is the same type of thing that happens when people are under stress, only we are exhibiting our behavioral drives.“

The more strongly you exhibit a particular drive, the more heavily you will lean into it when pressure mounts. If you’re not careful, these instincts may cause you to behave counter to what the situation calls for.

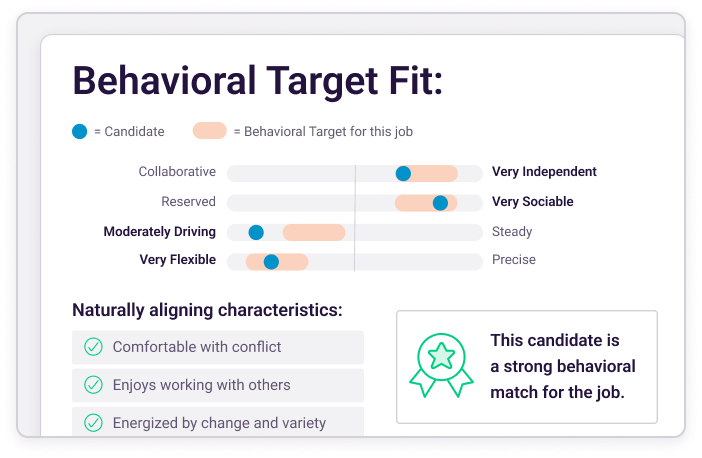

As a leader, you can do a couple things to combat this. First, familiarize (or re-familiarize) yourself with your behavioral profile. Note where your drives are most and least pronounced—and how the relationships between those drives might manifest. Are you a dominant, big-picture person, with lower levels of patience? You’re likely more comfortable taking risks under typical business circumstances.

But these aren’t typical circumstances. You’re under pressure, and probably considerable stress. Practice self-awareness; when you feel that stress building, take a step back and ask yourself: Is this affecting the decisions I’m about to make for the team?

“Even in the best of times, self-awareness is critical for leaders,” says Tom Riggs, CEO of Mindwire and a PI Certified Partner. “They need an accurate picture of their own needs, drives, and strengths so they can understand what they do well, what they need, and how their particular behaviors impact others.”

Understanding yourself as a leader allows you to do what’s ultimately essential in any crisis: adjust.

Recognize when you start to stretch.

You can still leverage your strongest behaviors for the greater good in crisis. For example, if you’re a highly patient leader, that drive will be a boon in times of anxiety. Your even-keeled, steadying influence may help calm people and stem knee-jerk reactions. But at a certain point, a measured approach needs to give way to decisive action, particularly when the economic impact of a crisis is so rapidly evolving.

If you’re a dominant, risk-taking individual, that could be detrimental to the team as well. You may be inclined to take chances at a time when the stakes for every decision are raised.

In the most egregious cases, dominant individuals will want to call the shots, ignoring others and stoking conflict. They become impatient and more authoritative, prioritizing swift action and overlooking feedback. Granted, they may not mean to be dismissive; they’re simply under stress and doing what comes most naturally.

“In crisis, our flight response system is triggered and those needs and drives are going to be on full throttle in terms of how strongly they are felt by a person, and how strongly they will need to be expressed,” Riggs notes. “And that doesn’t always result in these behaviors being manifested as strengths.”

Check this behavior in yourself as a leader. It’s imperative to do so before it actually exacerbates the crisis. Instinctual reactions can cause your employees more stress and disruption—particularly if they don’t understand how or why this is happening.

If you allow this instinct to narrow your executive function too much, Riggs explains, you may become more steamroller than superhero:

“Instead of a cool, calm, collected Bruce Banner, with plenty of executive-functioning brain [power] controlling things, the fight/flight response triggers the ‘Hulk Brain’ version of us—everything is in overdrive.”

Balance your behaviors with complementary drives and people.

Not all your natural behaviors as a leader will need to be dialed back. Confidence and perspective, or a sense of pragmatic optimism, can help reinvigorate your people.

But no one leader can navigate a crisis alone. As Friday notes, this is why some form of corporate governance is important. During times of stress, a balanced leadership team can help knock down “ego barriers” and enforce a system of checks and balances.

You may not realize your blind spots, or where your drives are actually limiting the broader group. People with complementary drives can mitigate the urge to go beyond your natural scope. A well-rounded leadership team will:

- Lean on people in their areas of expertise.

- Stress-test important decisions by running them by people with different perspectives.

- Pick each other up while holding one another accountable.

“This is often called believability-weighted decision-making.” Friday explains. “People who are most believable or experienced in an area should have their opinion weighted more heavily. Many leaders don’t accept this due to the ego barrier.”

“Do an honest accounting of how we’re each showing up—including asking others for honest feedback about whether we’re in the ‘Hulk Brain’ version of ourselves,” Riggs adds. “It’s going to be impossible for leaders to regulate themselves, and get back to executive brain function.”

There’s no room for egos or Hulk Brains right now. The businesses that endure this economic downturn will be the ones whose leaders have acted with awareness of their own drives, at a sustainable pace, while leveraging the best of the people around them.

cl