Victor Lipman is a management trainer and author. His online course on Udemy is The Manager’s Mindset and his book is “The Type B Manager.” He has more than 20 years of Fortune 500 management experience. He contributes regularly to Forbes and Psychology Today, and his work has appeared in Harvard Business Review.

Dealing with management conflict is something I know a fair amount about. Early in my management career, a mentor of mine took me aside. He praised my abilities (my knowledge of our business and my work ethic) but told me straight-out that for me to succeed in management, I was going to have to be able to deal with conflict more effectively. Today, more than two decades later, I still remember his exact words.

“I just don’t know if you can handle conflict,” he said. “Frankly, I don’t know if you want to handle conflict. I don’t know if you have the stomach for it. Because so much of management, particularly at the higher levels, involves dealing with conflict on a regular basis. Can you see yourself doing that?”

He was a fine mentor and he was 100 percent right. I was avoiding conflict more than I should have been. Conflict was stressful. It was easier to avoid it and get along with people. But as I came to realize more clearly over time, simply “getting along with people” wasn’t the job of management.

Management is about getting results. Getting positive results on an ongoing basis. As I often like to say, management is nothing if not a results-oriented endeavor.

Conflict as the everyday fabric of business

So why is conflict an inherent element of the managerial process? Think about common manager tasks:

- Managers need to take corrective actions.

- Managers need to candidly evaluate employee performance.

- Managers need to allocate scarce resources.

- Managers need to make hard personnel decisions about who does what, and why.

- Managers need to hold people accountable.

The bottom line is that managers need to manage.

All of these essential functions can involve employee pushback. And differences of opinion, and disagreements. Or competition with other managers, and disputes.

In a word: conflict.

Conflict may often be nothing dramatic, just the everyday fabric of work getting done. It’s the thread from which the cloth of business is made.

Effective, successful managers recognize this and know how to handle conflict. Fairly, firmly, and diplomatically—without undue drama.

They deal with it. They don’t avoid it. They don’t steamroll it. They handle it.

Managing conflict is an issue more of will than of ability.

As my mentor told me, if I was going to succeed in management (which I definitely knew I wanted to do—I had a young family to support), I was going to have to handle conflict. So I did.

I worked at it diligently.

I prepared myself (emotionally as well as technically) for meetings and confrontations I sensed could be difficult.

I accepted that conflict went with the territory, and I would do what I had to do and try not to take it home with me.

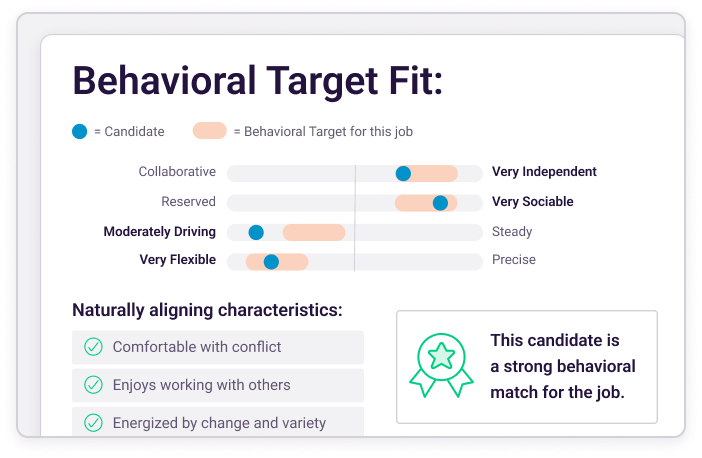

Join 10,000 companies solving the most complex people problems with PI.

Hire the right people, inspire their best work, design dream teams, and sustain engagement for the long haul.

At the end of the day, managing conflict is an issue more of will than of ability.

You just have to get your mind in the right space to deal with it. I came to view conflict as part of the normal course of business events, nothing overly emotional.

As my career progressed and I moved into executive ranks, did I ever really like dealing with conflict? Not especially, can’t say I did. Most people don’t. But I learned to compartmentalize it and accept it as part of the role. Was it a strength of mine? No, I wouldn’t say that. But was it a glaring weakness? No, not that either. I became competent, and capable enough.

I came to accept conflict as part of the job of management. And an important part at that.

Victor Lipman is a management trainer and author. His online course on Udemy is The Manager’s Mindset and his book is “The Type B Manager.” He has more than 20 years of Fortune 500 management experience. He contributes regularly to Forbes and Psychology Today, and his work has appeared in Harvard Business Review.